This is an analysis by Maja van der Velden who works at our member organisation Sustainability & Design Lab within the University of Oslo.

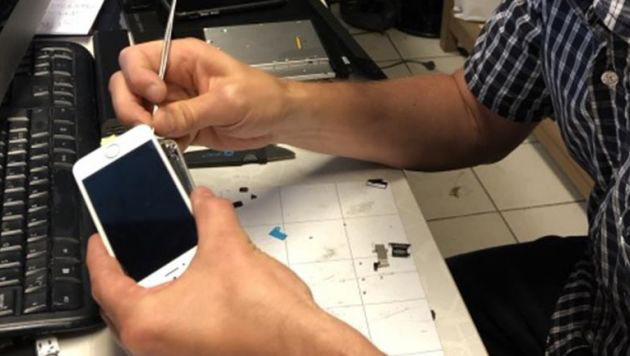

On June 2, the Supreme Court upheld the decision by the Appeal Court in concluding that Henrik Huseby, owner/operator of a small electronics repair shop in Ski, violated section 4 of Norway’s Trademark law by importing 63 iPhone compatible screens that had concealed, counterfeit Apple logos.

The Supreme Court concluded that the concealment, which consisted of black ink used to cover the Apple logos, could be removed easily, thus enabling Huseby to misuse Apple’s trademark and sell these screens, which Apple argued were fakes, as genuine Apple parts. The trademarks mentioned in the decision are in fact obscure tiny Apple logos printed on the parts of the screen that are inside iPhones and which remain invisible to consumers. The concealment of logos with ink is a practice often used by refurbishing companies to avoid violating trademark laws and to create a no-name spare part.

The invisibility of the tiny logos inside the mobile phone convinced the Oslo District Court, which ruled in Huseby’s favour. Apple’s appeal of the initial decision prepared the stage for a David and Goliath battle in the Norwegian court system that reached the opposite outcome of the biblical story and inflicted a heavy defeat for electronics repair around the world. The battle reached its conclusion with the Supreme Court accepting Apple’s argument that independent repairers could remove the ink on the logos and resell the screens as genuine iPhone screens.

It is striking to see that the Supreme Court’s decision is based on a basic ignorance of the iPhone spare part market. The reality is that Apple has a monopoly on genuine iPhone spare parts, a fact well-known by independent repairers and iPhone owners. Because they don’t have access to genuine iPhone screens, the only recourse for independent repairers is to import iPhone-compatible screens, which come in different prices and qualities. One type of compatible screens are refurbished screens, which often have some original components. These may still carry a tiny Apple logo, but it is widely acknowledged that these are not genuine Apple parts. In this market for spare parts, the existence of an Apple logo, concealed or not, has no effect on the perceived costs or quality of these compatible parts.

By not allowing independent assessment of the screens imported by Huseby and ultimately not addressing whether they included mostly refurbished components, the Supreme Court leaves a lot of questions unanswered for the independent repair sector.

The Huseby case revolves around Apple’s attempt to ensure it monopolises the entire repair market. Apple’s policy contrast with normal people’s expectations that repair is something we should all have access to. The Supreme Court’s decision shows how a powerful global market actor is able to use Norwegian trademark law to confirm and strengthen the control over the repair of its products and to hinder the development of a much-needed repair culture in electronics. The Court’s decision is expected to have a chilling effect on all independent electronics repairers who import iPhone compatible spare parts.

The decision is most unfortunate from a sustainability perspective. The Supreme Court states in its decision that sustainability doesn’t play a role in this case, because independent repairers can import iPhone-compatible screens without Apple logos. However, from a sustainability perspective, using refurbished screens is clearly a superior solution to using newly manufactured ones. Here the Court’s decision has created further risks to the import of refurbished screens and, in effect, tilted the balance in favour of the least sustainable option.

That Apple wants to keep control of the repair of its phones is not surprising. In 2019, over one million iPhones were sold in Norway and 185 million worldwide. With a monopoly on spare parts, Apple can decide the price of its repairs, both for its own repair services as those of Apple-authorised repair shops. They can keep repair prices high in order to create incentives for people to buy new models, instead of repairing them. This only perpetuates a culture of throw-away electronics, which goes against the goal of sustainable production and consumption.

Apple is very active in opposing the so-called right to repair legislation, in Europe and the US, which would require Apple to make repair information and spare parts available to all repairers. Printing tiny Apple logos on the different parts of iPhone screens is a way to fight the right to repair movement by using national trademark laws, like in Norway, to deny independent repair shops access to refurbished spare parts.

The role of a trademark is to protect a brand and to promote competition by indicating to consumers the maker of the product. The effect of Apple’s use of trademark law, and its opposition to the right to repair, is to stifle competition in the repair sector, with the effect that consumers are likely to have less choice and pay more for repairs. The Norwegian Supreme Court has ruled that tiny logos inside a mobile phone, that are invisible to consumers and irrelevant to independent repairers, are somehow a violation of Apple’s trademark. The decision is a costly one for Henrik Huseby, who will have to pay damages to the world’s wealthiest corporation. But it is also costly for Norwegian consumers and for sustainability in general.

So Henik buys 63 screens with Fake “counterfeit” logos for a lower cost than “genuine” replacement parts. Was his repair less or equal to his previous service charges when he used “generic” Apple authorized parts? If repair costs weren’t lower intent to profit from “grey” market distribution is a a poor choice. But really shouldn’t Apple climb the tree and deal with the “counterfeiters”,

Goliath versus Goliath? Sorry Henrik.